What if we told you that swimming could be a martial art, and a swimmer—a warrior? That during swimming, one could shoot a bow, wield a sword, or engage in hand-to-hand combat? In the latest installment of our "Swimming Journeys" series, we present Nihon Eiho, derived from the samurai martial art of fighting in water, Suieijutsu. Our guides on this topic are first-degree practitioners—Piotr Kieżun and Paweł Rurak (Paul Piper's)—who visited Japan and practiced this unique form of swimming there.

Is Swimming a Martial Art?

What exactly is Nihon Eiho? Is it more of an art or a combat technique?

Piotr Kieżun: Modern-day Nihon Eiho, practiced in Japan, is more of an art than combat, although it originates from Suieijutsu (suiei – swimming, jutsu – art, skill, technique)—a military technique designed to prepare samurai for fighting in water.

Swimming and Technique

What does this activity in the water involve? What can it be compared to?

Paweł Rurak: If you search online for videos related to nihon eiho, you’ll typically find clips showcasing the diverse, traditional applications of Japanese swimming techniques. You might see swimming in full armor, shooting a bow or rifle while floating in the water, calligraphy demonstrations, waving a giant flag, or synchronized team swimming in formation. Most of these materials are for demonstration purposes—they reflect how samurai would showcase their skills to their Shogun.

The daily life of a nihon eiho swimmer is far less festive and much closer to the swimming training we’re familiar with at our local pools. Swimmers focus on several main techniques for moving in the water, each with numerous additional variations.

Training for a nihon eiho swimmer is heavily centered on technique, as precision in movements is key. Short distances are often swum repeatedly to achieve near-millimeter perfection. During our trip, when Piotrek and I were invited to train seriously, we were given 3-hour sessions. None of the athletes on our team (Keio University) seemed surprised by this rigorous schedule.

If we were to draw comparisons to techniques familiar from Western pools or television, parallels to synchronized swimming or water polo would immediately come to mind. Many nihon eiho techniques are also nearly identical to swimming methods occasionally seen among older swimmers in Western countries. For instance, many of them swim on their side, using a scissor kick, which forms the foundation of many Japanese swimming styles.

At the end of our trip, Piotrek and I were invited to participate in an official exam for the first level of nihon eiho, which was quite similar to earning different belt colors in karate.

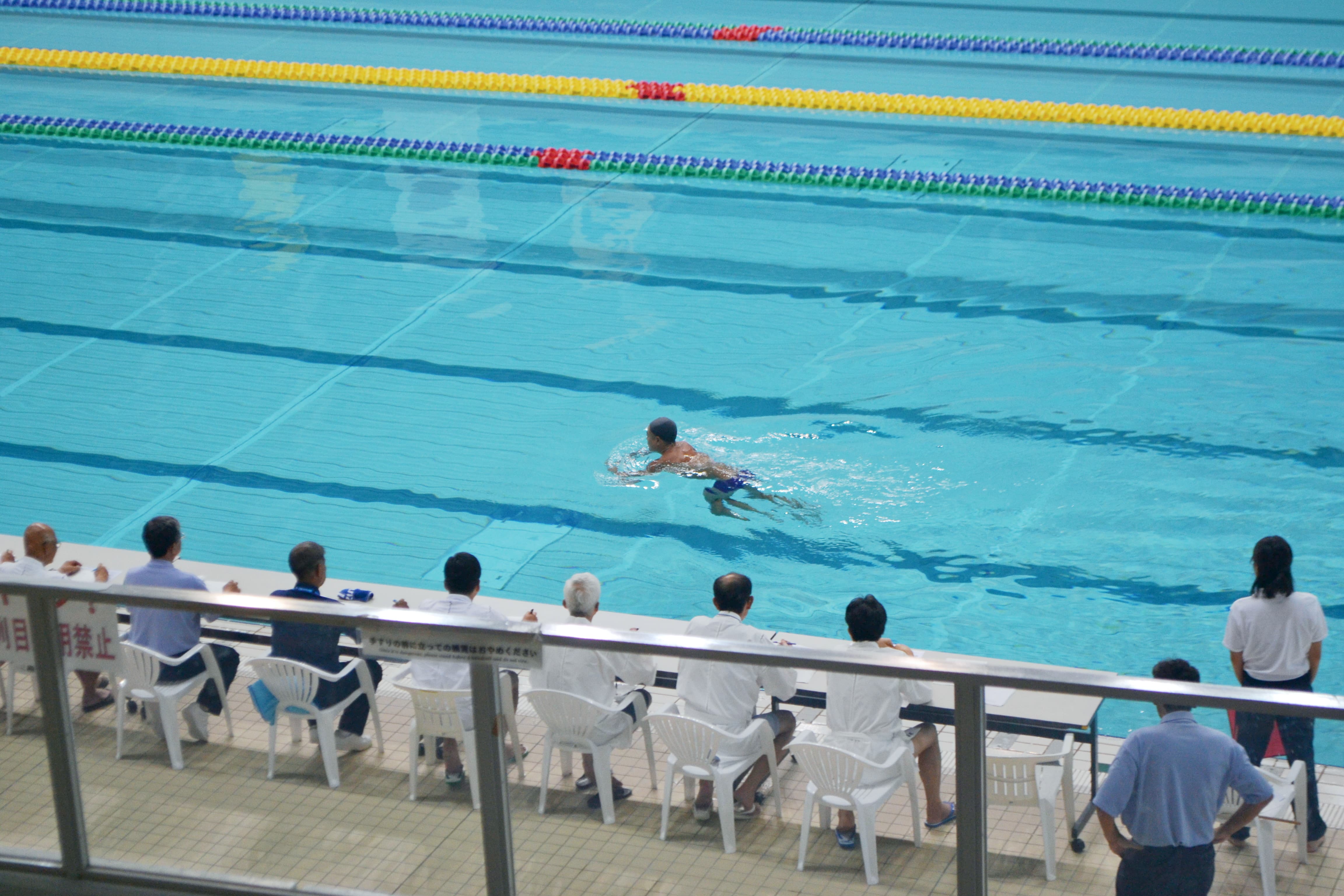

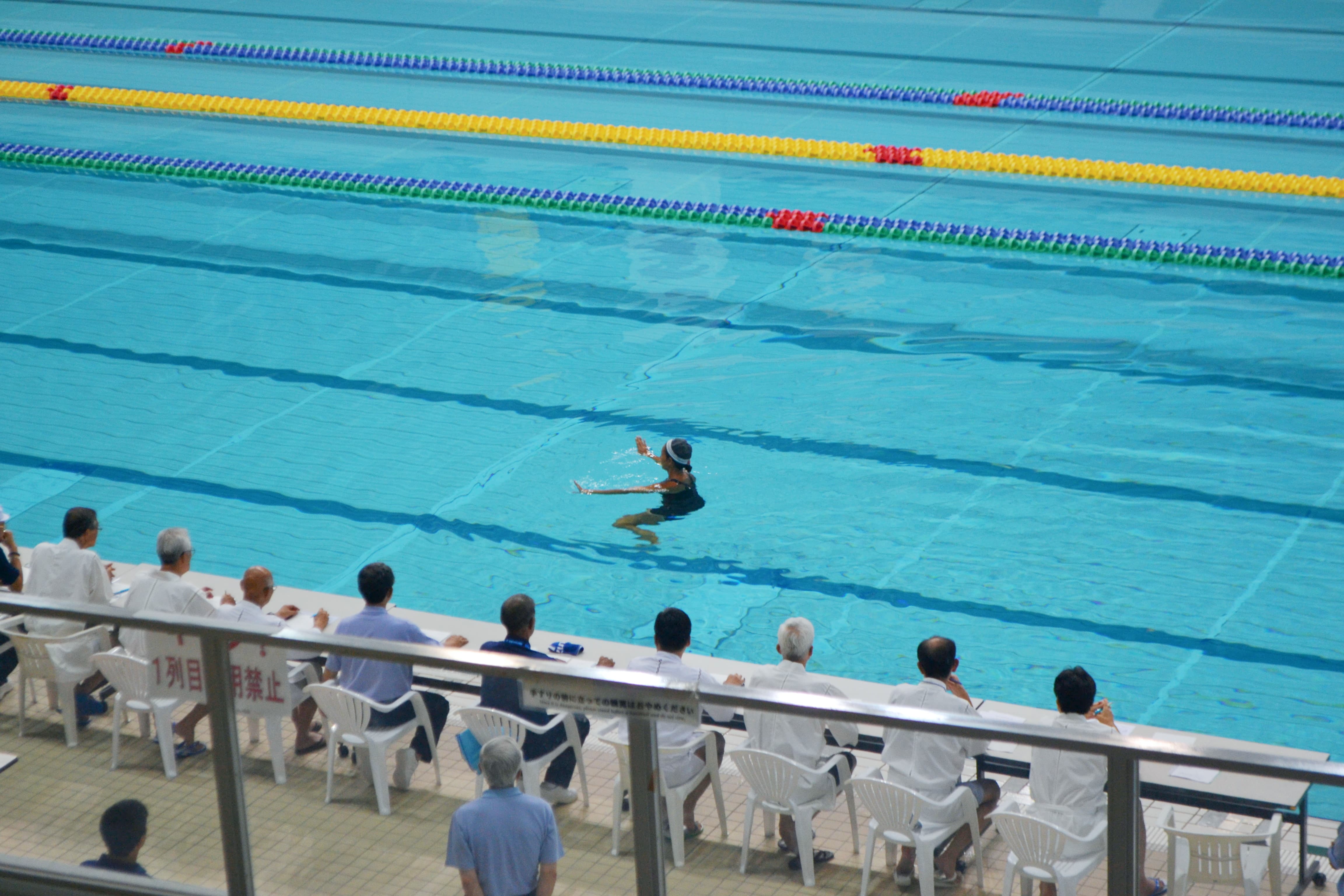

The exam took place during the annual Japan Championships, where we got to see firsthand how the competitions work. There are several events, but only one focuses on swimming speed. The rest evaluate precision. Exams run parallel to the competitions, and ours involved demonstrating two techniques before a panel of 13 judges—each representing a different school of nihon eiho.

I admit that despite my experience in competitive swimming, I was a little nervous. The kind of “start” and focus required was entirely different from swimming 200 meters freestyle.

Water Safety

How do nihon eiho techniques relate to water safety? Could it be a way to promote swimming and safe interaction with water among youth?

Piotr Kieżun: Midori Ishibiki, a nihon eiho coach and judge we met in Yokohama, repeatedly emphasized that Japanese swimming is not just a sport but also an attempt to find harmony between the body and water. To achieve this, muscles are important, but so is the mind—how we think about water and in water, our respect for this element, understanding how our body behaves in it, and learning what to do to make water our friend, not our enemy.

In a book about the history of nihon eiho that Midori gave us, there’s a quote from an old samurai “Book on the Art of Navigation” that perfectly illustrates the philosophy of nihon eiho: “The most essential thing in swimming is to move in water without tension; this is why the old saying goes that the body and water follow the mind.”

This means that building a positive and responsible attitude toward swimming and moving in water is the first point where nihon eiho aligns with the expectations of young swimmers—and perhaps even more so with their parents, who may worry about their children’s safety.

The second point is more practical. Nihon eiho is highly versatile. Its countless techniques allow swimmers to adapt to various conditions. After all, Japanese swimming didn’t originate as a pool sport. It’s more akin to traditional open water swimming. Swimmers had to learn how to handle rough seas, fast river currents, or whirlpools.

In most techniques, maintaining the head above water and having the freedom to use both hands is crucial. This greatly enhances the sense of safety and control, though respect for water remains the most important factor. I remember how strongly this was emphasized by swimmers from Tokyo Bay, who swam in the ocean.

There’s also a third reason why nihon eiho can appeal to young people. Who wouldn’t, even for a moment, want to walk the path of a samurai, knowing that the tradition they practice is over 400 years old? Nihon eiho is not just swimming—it comes with a rich cultural context: history, rituals, and ceremonies.

A member of a school who passes the first-level exam receives a suikan—a type of traditional kimono for swimmers, used in official settings (competitions, judging, etc.), with a unique design for each school. At nihon eiho championships, participants bow to the judges before entering the water and then bow to the pool, which here serves as a dojo—a training space that, like in any martial art, deserves respect.

All of this creates an unforgettable atmosphere and a sense of participating in something extraordinary. But it’s important not to overstate this sense of uniqueness. Nihon eiho, like any form of swimming, is simply a way of life—a daily activity that anyone can practice regularly.

Interview by: Maciej Mazerant / Editor-in-Chief of AQUA SPEED Magazine

Photos from the archives of Piotr and Paweł.

Piotr Kieżun – A member of the Mako Sports Club, swimming enthusiast, and aficionado of the history of this sport. He proudly holds a first-degree certificate in nihon eiho (Suifu school). When he’s not swimming, he serves as an editor at the weekly magazine Kultura Liberalna, where he heads the book review section. His work focuses on French literature.

Paweł Rurak – A swimming coach at the Mako Sports Club and a promoter of holistic development (not just physical). He believes it’s never too late to learn new skills. His passion lies in storytelling about swimming and the broader concept of physical culture, many of which can be found on his blog.